Science fiction tends to fall into one of two camps.

Hard sci-fi aims to be science-accurate, which is why it's stereotyped as boring. That's painting with a large brush, but at the same time, if I wanted science lessons, I'd watch Neil deGrasse Tyson's YouTube channel. (Which is another way of saying I don't want science lessons.)

The Martian is an example of great hard sci-fi because it's very science-y and also super entertaining. In fact, the science is what makes the story so good. I've never been more engaged with math in a fictional story—or, truth be told, math ever—than when Mark Watney determines how long he can survive on potatoes grown from his own fecal supply. It brings the farm to table concept full circle.

(The novel is more scientifically sound, but the film is close enough for most science geeks. For my money, Andy Weir is the best hard science fiction writer because while the science is entirely plausible, it takes a back seat to story and characters. And also because he's hilarious. Project Hail Mary is a crazy-good story, even better than The Martian, and is currently filming for a 2026 release; the movie stars Ryan Gosling and the girl from the AT&T commercials.)

Then there's soft sci-fi, so noted because it don't need no stinking rules.

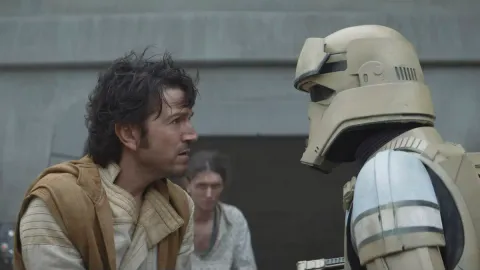

Technically, the moniker signals an emphasis on soft sciences like psychology or political science, but in practice, it means the story can invent its own rules. Universal laws such as gravity, the vacuum of space, and time dilation all bend the knee to character and plot. The laws are whatever the story requires them to be, and therefore are really more like loose guidelines. This is precisely why outer space in Star Wars is so exciting. TIE Fighters scream. X-Wings pew-pew. The edge of the galaxy can be reached in mere hours. None of this is accurate, but it doesn't matter because it's awesome.

You'd be forgiven for thinking Star Wars is soft sci-fi.

It's appropriately futuristic, with spaceships and droids and a clear opposition to fascism. But despite all the trappings, Star Wars isn't sci-fi at all. (Technically it falls into the space opera subgenre, but that's really just a way of extending the science fiction umbrella to cover edge cases it rather wouldn't, but feels compelled to because they occur in outer space, and thus, technically part of its jurisdiction.)

Star Wars is a fantasy fairy tale

There are some obvious signs.

Star Wars takes place a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away, which is just a different way of saying, "Once upon a time."

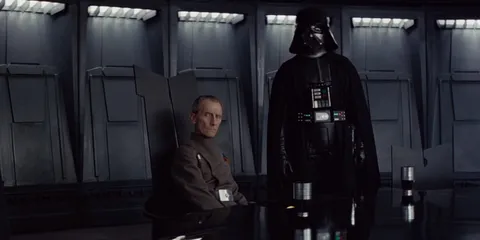

Star Wars has magic. The Prequels try to put a science spin on the Force by making it a rare blood condition, but George Lucas never really commits to the bit. Related: Even though everyone is running around with laser guns, a few special people wield laser swords. This is sword and sorcery, people!

By the way, these sword-wielding magic-users are called Knights.

This magic can be used for good (white robes) or bad (black robes). When used for evil, the magic corrupts the wielder. Most fairy tales are lessons in morality.

The plot of the first Star Wars movie hinges on rescuing a princess. Don't be distracted by how Leia subverts the "damsel in distress" trope by bossing the boys around and taking charge during a shootout. A princess who needs rescuing is Fairy Tale 101.

Luke Skywalker follows the mythic hero's journey, which forms the basis of nearly every traditional fantasy story you've ever heard of; fantasy stories are the teenage version of fairy tales.