It’s common to look back at your younger years and think, “life sure was simpler.”

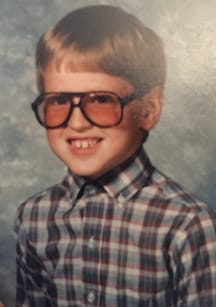

In the 80s, my biggest decision was deciding between Pop Tarts and Corn Pops. I was also still eating my own boogers—getting high on my own supply—so life wasn't exactly stressful.

Simpler doesn’t usually mean better. Case in point: our childhood entertainment.

In the 80s we did not give a shit about verisimilitude.

Stories didn’t need to make sense. They just needed to be awesome. Which is how you get a show about a sentient Trans Am and its best friend, David Hasselhoff. Or comedies in which a suburban family civilizes a creature that would eat them in reality (A.L.F., Harry and the Hendersons). Or movies about famous bouncers, or time-traveling doofuses, or nerds who turn a Barbie into Kelly LeBrock.

These stories didn’t just ask you to suspend your disbelief—they asked you to believe in the impossible.

Cocaine is a hell of a drug. Just look what it did to Star Wars.

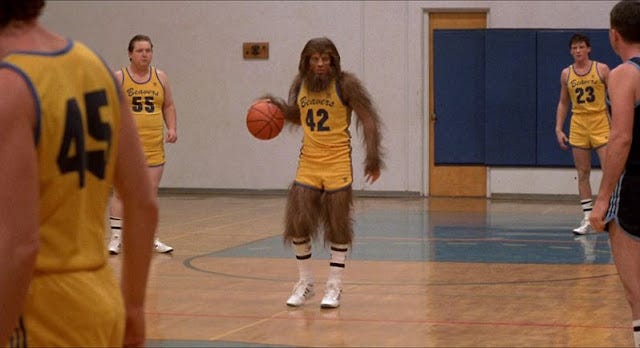

Which brings us to Teen Wolf, a movie so ridiculous I’m inventing a new metric by which to measure this sort of thing: SPM (shenanigans per minute). Given the 92-minute runtime and the utter insanity that occurs on screen, Teen Wolf has to be a top-5 SPM film.

A partial list of ridiculous things the movie asks you to buy:

- Someone turns into a werewolf during a basketball game… and the game just continues.

- One of the secondary characters is called Chubbs because he’s a bit rotund. Everyone calls him Chubbs: his friends, the other basketball players, the coach. Probably even his mom. Is Chubbs on his birth certificate?

- The main character shows up late to the championship basketball game and they immediately stage a new tip-off because obviously whatever happened before doesn’t count. The score remains though for dramatic reasons.

- The game ends with a foul. Everyone leaves the court except the guy who was called for the foul. He’s allowed to stand under the basket and glare at the main character as he shoots free throws.

- The hot girl likes guys with aggressive body hair, yellow claws, and legit canines.

- The best friend seriously wants to hold-up a liquor store with a water gun. There’s no thought of repercussions because he’s a white goofball. Harmless.

- The thing 80s teenagers most liked to do at parties was writhe around in whipped cream in their underwear while their peers stand around in a circle.

- The main character’s dad is also a werewolf. In fact, they come from a long line of werewolves. Somehow this isn’t common knowledge or even a rumor. “Stay away from those Howards—I heard they howl at the moon and lick their own nethers.”

- The vice principal knows about the dad’s midnight tendencies and is deathly afraid of him, but he still antagonizes the son because he’s a vice principal.

Perhaps my favorite moment: Dad Howard gives Scott Howard (Michael J. Fox) the Spider-Man talk—with great power comes great responsibility—but 10 minutes later, Scott Wolf steals the basketball from his own teammate. It’s the greatest cinematic betrayal since Lando Calrissian traded Han Solo’s freedom for a block of government cheese.

I guess the message is absolute power corrupts absolutely. Or perhaps: If you allow a werewolf to play team sports, you can’t get mad when he lone wolves it.

Teen Wolf is a bad movie. But it’s a watchable bad movie. You will feel your brain cells committing suicide but you won’t mind terribly because the movie is kinda fun.

This movie lives and dies on one thing: the megawatt charisma and physical comedy of Michael J. Fox. He was in the midst of his Family Ties run as Alex P. Keaton, a hardcore Republican living with hippie liberal parents. He filmed Teen Wolf the last two months of 1984 and by mid-January was working on Back to the Future. Both films briefly played in theaters simultaneously. 1985 was both Fox’s official arrival as an up-and-coming star and the apex of his stardom.

These two films are linked only due to proximity. Back to the Future is an impeccable film. Teen Wolf is a bad joke played out over 90 minutes. It came out at a time when Fox was still clearly on the ascent. His filmography through the rest of the 80s is a mishmash strange choices (Casualties of War), movies I’ve never heard of (Light of Day; Bright Lights, Big City), and, of course, the Back to the Future sequels. The only standout is The Secret of My Success, which isn’t necessarily a good movie. It just takes advantage of the inherent boyishness at the heart of Fox, which is roughly 80% of his appeal.

Watching Teen Wolf is a glimpse into a past with as-of-yet infinite possibilities for Fox’s future. I can appreciate his desire to not be typecast as an adolescent heartthrob—a demographic that ages out super fast; anyone seen Jonathan Taylor Thomas lately?—but knowing how short his window ended up being, I wish he’d avoided dramas and war pictures in favor of movies like Teen Wolf. Because it turns out that’s his sweet spot.

Once you get past the batshit premise—and thanks entirely to Fox’s performance—Teen Wolf is pretty enjoyable. It’s a bog standard teenage coming-of-age story with casual yet clear shades of beastiality. I found myself thinking about Can’t Buy Me Love and not just because Ronald Miller (Patrick Dempsey) also has wild man vibes.

Both films involve the glow up of a high school dork into the most popular kid in school through means and ways that seem highly suspect. It’s an evergreen premise that got a lot of mileage in the 80s, I guess because our schools were lousy with nerds. Or maybe my antenna was just attuned to pick up signals that offered hope for the socially downtrodden.

Both films also have a nougaty-like moral message buried under layers of hijinks and sex-up teenage antics: People may be wowed by the showy persona, and coerced into a ridiculous dance number simply because someone popular is leading the way, but it’s all empty calories. Popularity is fleeting and vapid.

Of course it’s easy to make such sweeping statements from the comfort of my home office, surrounded by the assured isolation of adulthood. Popularity now is a meaningless metric. Much harder when you’re in high school and have to deal with popularity’s very-real currency; render unto the prom king the things which are the prom king’s, and unto the nerd a wedgie or perhaps wet willy.

Ronald Miller does not give up his crown willingly. Scott Howard abdicates because he is increasingly uncomfortable with the divide between who everyone wants him to be (the wolf) and who he actually is (the dork). When he dares rehearse for the school play as Scott, the director is incensed. “No one wants to see you.” What a horribly cruel thing to say. But it’s true. For 99% of the school, it’s the wolf or nothing.

This, ultimately, is the hardest part of the movie to accept. If you’ve ever attended a school or even a gathering of two or three children, you know that Being Different is not considered an asset. The goal of high school is to fit in, to not stand out, because the poor bastards on the periphery are easy targets. This may not be as true today, but it was the way of life in the 80s. So the idea that high schoolers would embrace Scott Wolf specifically because he’s a hairy monster doesn’t hold water. I mean, yes—it’s great that he can dunk. And shotgunning a beer by biting it is a neat trick. But becoming a popular kid? With his own merch? Nah, dawg.

Sorry—nah, wolf.

There was a kid in my high school who didn’t shave his whiskers. And at the length he wore them, they were 100% whiskers. And because he was a teenager, his facial hair was spotty. Just a bad look all around.

My brother and I called him Wolf-man. Not to his face. But we giggled about it whenever we saw him. And sometimes we howled. The memory embarrasses me now. At the time I thought nothing of it. Teenagers have the capacity for great cruelty.

So I don’t buy everyone at school going wolf-crazy, or the hot blonde sleeping with Scott if he wolfs out first (so gross, maybe someone can explain that one to me). Teen Wolf asks you to accept the idea that a high school wolf-man would be celebrated for being so wildly different. But that wasn’t what life was like in the 80s, and it’s not in the 2020s either.

In reality, people fear what’s different. Fear leads to hate. That’s Star Wars 101, but also real life. If Scott Howard actually turned into a werewolf in the 80s, he would’ve been mocked at best. Socially ostracized, certainly. Possibly whisked away by government operatives for study and dissection. It would not be happy ending.

If it happened today, someone would kill him. I can say that with absolute certainty. I don’t know how you look at the hatred people have for those who look slightly different, or vote differently, and come to any other conclusion. People be cray and are packing heat.

Considering the real-world implications of a high school werewolf is a flimsy bar to hang an argument on. I’ve used worse. But films of the era offer a time capsule of what life was like at the time. Idyllic or no, it’s our only real way of time traveling.

So yes, in terms of the survivability of a teenage werewolf, life was simpler in the 80s. But I think it was for the rest of us too. Even if we were on the outside looking in, living vicariously through geek-to-chic movies, dreaming of our own come-up. No existential dangers, no fucking Nazis, just life.

We didn’t know how good we had it.

In closing, there’s one other story thread I’d like to consider on its own merits.

We learn fairly early that Scott’s dad is also a werewolf. He spends most of the rest of the film trying to reach his son and explain their condition. Scott ain’t really having it because adults are lame, and also because the cute blonde is suddenly noticing him. Everything’s coming up wolfsbane.

It made me realize how often fathers pass their struggles onto their sons. It’s unintentional, an alchemy of genetics and lived experience passed via osmosis. But as Shakespeare said, the sins of the father are laid upon the children.

My father had a temper. Blame it on nature or nurture, but I have one, too. Imagine my surprise and shameful disappointment the first time I heard my son slamming his desk in frustration while playing a video game. Fruitless, directionless rage—ah, I know it well.

It’s tempting to use the Howard clan’s werewolfitis as an analogy for anger. It’s right there and also obvious. But apart from a few brief glimpses of rage, it doesn’t really line up. The most notable instance is when Scott loses his crap and attacks his blonde booty call’s boyfriend. The dude had it coming, but Scott blacks out in his rage. If I can apply a Star Wars metaphor: He was more wolf than man, twisted and evil. But mostly, the werewolf is a tame beast who wants to party.

What I keep coming back to is the dad’s quiet disappointment when he realized he’d passed this burden onto his son. The pain of it, the resignation, the sadness. We want the best for our kids but sometimes they get our worst.

I think all fathers are quietly afraid of damaging their children. We don’t have the maternal instinct; the paternal instinct mostly involves a lot of farting. For most men, the first baby we ever hold is our own. That’s an awesome responsibility we’ve done literally nothing to prepare for. So we do the best we can, and sort of hold our breath to see how they turn out.

Mine turned out good. I’m proud of the people they are becoming. But, like Scott’s dad, I wish the Pierce temper sat this generation out.

I’ll be totally honest—I threw on Teen Wolf expecting to laugh at the ridiculousness of it all. And I did. But mostly it left me feeling a certain kind of way about life.

It’s interesting that in all the times I’ve seen his movie, I’ve never once considered the dad’s point of view. I was too busy living it up with my guy Michael J. Fox. But now it’s all I can think about.

Pretty good for a 40-year-old movie about a teenage werewolf getting laid.